11 Summative Assessment: Qualitative report

11.1 Report Writing Guide

This section is intended to help you in the write up of your qualitative project report. When writing your report, remember to use the other resources available to you:

- Chapter 13 in Braun & Clarke (2013) is excellent support for writing up qualitative research

- The feedback your group received on your group proposal

- The feedback you received from RM1

- Braun & Clark (2021) book

- Helpful resources for APA formatting are OWL Purdue and APA Style

- We have developed a resource of Frequently Asked Questions from previous cohorts

- Student Learning Development have useful information about writing for students

If you have further questions, post on Teams and/or visit your tutor’s office hours. All the best in writing your report.

11.1.1 Required Submissions

Two separate submissions are required for this report:

-

Submission 1 should contain the report itself, along with the specified sections and appendices.

- Cover page with title (does not count towards the word limit)

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Method

- Analysis

- Discussion

- References (does not count towards word limit)

- Appendices (does not count towards word limit)

-

Submission 2 should contain the required information about the process of your analysis, using the template provided. Submission 2 does not count towards the word limit. Please note that Phase 6 is not included as this is what you include in your Analysis section

- Phase 1 (Familiarisation)

- Phase 2 (Doing Coding)

- Phase 3 (Generating Initial Themes)

- Phase 4 (Developing and Reviewing Themes)

- Phase 5 (Refining, Defining and Naming Themes)

11.1.2 Submission 1: The Qualitative Report

11.1.2.1 General writing style

Your writing should be clear, concise and easy to follow - remember that academic writing does not need to be complicated to be good. One tip is to use word to read your report back to you – sometimes it’s easier to hear where a point may be overly complex or long and where you might want to cut it down.

Maintain a neutral, academic tone throughout. Avoid a ‘journalistic’ tone, where you convince the reader based on using emotive language. Instead, show the reader why you think the way you do and the evidence base that underlies this.

Discuss one idea/argument per paragraph. An excellent resource to help with this is the reverse outline.

You should format your headings, in-text citations and references in APA 7th style.

APA writing style encourages the use of active voice (“I coded the data” rather than “the data were coded”) but if you feel more comfortable writing in passive voice, feel free to do so - just make sure to be consistent throughout and be careful not to make your writing overly complex.

Tenses are not always fixed per se (as it depends on how a sentence is structured). However, generally, the following applies – past tense should be used when you have done something already (like your study). For example, we would usually see past tense in the Methods (unless doing a registered report) and the Analysis section. When talking about papers that are already published (in the Intro and Discussion), again these would typically be in past tense.

You can use first person singular (I) or plural (we) in the report itself if you want to, but in the reflexivity section make sure to write in first person singular. This is because this is your reflection of your own positionality to the RQ and the data, and it’s often very personal.

11.1.2.2 Title

The title should be included as part of the cover page. It should reflect the research question(s) and define your sample (e.g., UG students experience of…). Try to be specific - your title should include:

- Who

- What

- How

Examples:

- A Thematic Analysis (how) of the panic attack experiences (what) of primary aged children in inner city Schools in the UK (who)

- Barriers and enablers to modifying sleep behaviour (what) in adolescents and young adults (who): A qualitative investigation (how)

11.1.2.3 Abstract (suggested word count: 100-150 words)

In an academic journal, the function of an abstract is to give readers a snapshot of the whole paper. They then use this to decide whether or not to read the full article. Therefore, you should make sure you cover all four main sections of your report, summarising them all succinctly.

Aim to summarise all sections of the report in 150 words, including; 1) what does the existing literature tell us about the topic 2) aim of the study 3) brief methodology, 4) approach to analysis , 5) main findings, and 6) key aspects of the discussion. Keep in mind that you are summarising your research for a non-expert and you want to “entice” them to read more.

11.1.2.4 Introduction (suggested word count 750-850 words)

Some activities to support you with writing your introduction section can be found in Chapter 9 and lab 7.

The introduction should give readers enough background to understand your rationale for further research, whether your study is qualitative or quantitative. Provide a clear, critical review of the most relevant published research and highlight the key issues and debates in the field. Use these to build a logical argument for your study.

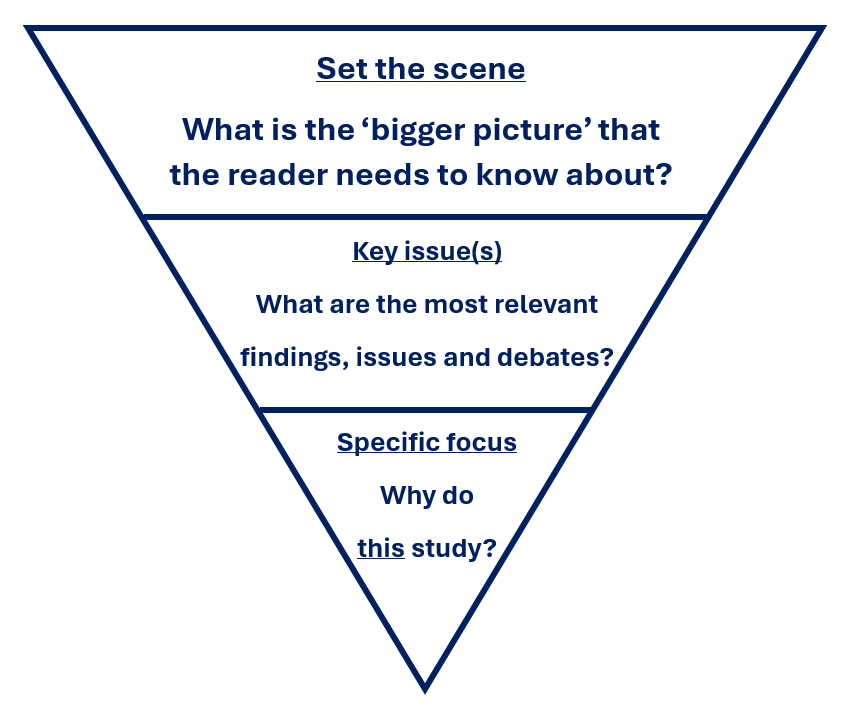

Follow the APA-style funnel structure: begin with a broad overview of the topic, then narrow the focus until you reach your specific rationale and research question(s).

Because your word count is limited, focus on recent and directly relevant studies—especially the latest research in this specific area. Show how your project builds on the most recent work to strengthen your rationale. Remember to cite all sources used, including government reports, websites, and media items.

You should end with a statement of what the aim of your study was, and the research question.

When reviewing previous studies, don’t just describe them - evaluate them. Highlight their limitations, but only those your study can realistically address. Consider what the findings mean, note any conflicting results, and think about why they differ. This should naturally build toward a clear rationale for your own study.

Then, explain your study and clearly state your research question(s), ensuring they connect directly to the issues raised in your introduction.

In summary:

- Review and critically evaluate relevant theories and research.

- Justify your study by linking gaps or limitations in past work to your research questions.

- Clearly outline your main and subsidiary research questions, ensuring these are phrased in a way that aligns with a qualitative approach.

Remember: just like in a quantitative report, this section shows what has been done before and why your study is needed.

11.1.2.5 Method (suggested word count: 350-450 words)

The aim of the method section is to clearly report how your study was conducted – the reader should be able to re-run your research from the details provided. In this case, report details of your focus group and the qualitative analysis you used. True ‘replication’ is difficult due to central role of researcher in influencing some aspects of the research such as analysis. This is not an experiment.

Participants & Recruitment

How many, who were they? Include their age, gender and nationality if known. How were they sampled? Why were your participants right for the study? In this study, participants were sampled from a group of PG students as part of their course requirements. A table of relevant participant characteristics is recommended. APA Styles has more information about how to report tables in APA format

Data Collection

What materials did you use to run the focus group? What information was given to participants? How was the focus group recorded, and how long did it take? Tell the reader about your approach to this, did you follow rapport building guidelines? Refer to the focus group questions in the appendices.

Ethics

Include a brief account of the ethical procedures and consider both ‘formal ethics’ (getting consent) as well as more nuanced ‘non-formal’ such as the rapport building, consent as a process and reflective practices of researcher (this may warrant its own sub-heading).

Reflexivity

In qualitative research it is important to acknowledge the role of the researcher in interpretation of the data (Elliot et al., 1999).

This is where you question your own motives and attitudes in doing this project. Obviously we told you that you had to do it. But, what motivated you to choose the dataset you did? What assumptions did you hold prior to beginning the research? Had you considered issues around the topic previously? Did they match what the interviews say, or did you disagree with them? Did this affect which interviews you chose to include in your analysis? And if so, how did this impact on your analysis? Because different people would interpret the data differently, it is useful for you to expose your own attitudes at this point so that others can see how you have impacted on the analysis.

See Braun & Clarke (2013, pp36-37, 303-304) and activities around reflexivity. Reflexive analysis should be concise for this project, perhaps around 3-4 sentences. However, you will also have to include a reflexivity diary as a part of your appendices - you can use your notes from this to help write the reflexivity section and give some examples, but please note the section should be much shorter than your full reflexivity diary.

Data Analysis

In this section, explain:

- What analysis method you used and your theoretical approach.

- The stages of your qualitative analysis. Be clear and specific - qualitative work is sometimes criticised for being vague. Use recognised guidelines (e.g., Smith for IPA; Braun & Clarke for Reflexive Thematic Analysis).

When outlining the stages:

- Give a brief summary of the full process, linked to the relevant framework (e.g., RTA). Around three to four sentences total is enough for this length of report.

- You can keep some phases short (e.g., “familiarisation with the data (Phase 1); generating codes (Phase 2)…”).

- Aim for transparency - explain what happens between coding and theme development.

- Describe the researcher as actively identifying themes, not waiting for themes to “emerge,” which incorrectly suggests they are already there waiting to be found.

11.1.2.6 Analysis (suggested word count: 750-900 words)

The analysis section is where you present the evidence you’ve collected. It works like a Results section in a quantitative report.

Your goal is to make the analysis transparent, showing clearly how your interpretations come from the transcripts. Use extracts from the transcripts to support all quotes and interpretations.

Guidelines

- Choose a maximum of two themes or one theme with two sub-themes to include in the Analysis section, even if you found more. You will not be able to go into enough depth if you present more themes than this, due to the word count restrictions.

- If you want to use parts of a quote, rather than the full quote (e.g. maybe you want to remove the middle sentence, which doesn’t add anything), you can indicate you omitted something with ellipses.

- Never alter any of the words or phrasing that is used, even if you think you know what the participant was going to say. This would be as unacceptable as editing numbers in a quantitative analysis!

- Try to strike a balance between quotes and interpretation. We sometimes see lots of quotes with very little analysis or lots of analysis with very few quotes, both of which have problems.

Do not, under any circumstances, put the transcripts or quotes from the transcripts into GenerativeAI (this includes CoPilot). This will not have been agreed as part of the original ethics and participants will not have consented for this use of the data.

Failing to follow these instructions puts you at risk of academic and research misconduct.

Structuring the Analysis section

- Start with a short paragraph summarising the main themes without using any quotes. This should not be too long - perhaps around a sentence or two.

- If you have two themes:

- Present each theme using a sub-heading

- Give the reader a brief overview of what the theme is. It is likely that you will have to select a few key points that encapsulate your theme, rather than describe everything in your theme in detail. For a dissertation, where you have more available word count, you will be able to cover more.

- Once you’ve introduced the theme, tell the reader about what you found in your analysis of this theme. Make sure to incorporate quotes to support your analytical points.

- If you have one theme and two sub-themes:

- Have sub-headings for the overall theme as well as the sub-themes.

- Briefly explain the overarching theme and then how the sub-themes relate to the larger theme. Do not present quotes at this point.

- Then, present each of the sub-themes in turn, under sub-headings. In each of these, tell the reader what you found in the analysis of your theme and incorporate quotes to support your analytical points.

Presenting Quotes

Use long quotes by placing them in a separate, centred indented block. Short quotes can be included within the sentence. Due to the word count, you are likely to be able to do a maximum of one or two longer quotes per theme or sub-theme.

You can find guidance on presenting participant quotes in APA format in the recommended resources. Although the word limit suggested here is 40 words, this is quite long and so we suggest taking it on a case by case basis (e.g. having a quote of 39 words within a sentence might be correct but also might be confusing to read). You can run anything past us if you are unsure.

We have also prepared an example of how to format quotes in APA style.

Going Beyond Paraphrasing

A strong analysis section will analyse the data, going beyond summary and paraphrasing. What do you add, as the analyst? You will have much more knowledge of the data, and it is your job to pass on that insight. If you paraphrase the data, the reader will be able to see this in the quotes, but the analysis then doesn’t add anything extra.

Instead of telling the reader what was talked about, explain what the things that were talked about reveal or suggest about the phenomenon you are studying.

Avoid writing themes that are topic summaries, as these are at a descriptive level.

- A theme of “Stress and workload” is mainly descriptive. It tells us the topics that participants mentioned, but not why they matter or how they relate.

- A theme of “Stress is an unavoidable requirement of ‘being a good student’” is interpretative. It goes further by explaining what stress means for the participants. For example, the data might show that students see stress as tied to their identity as students and that this is something that they expect, rather than something to avoid.

This kind of deeper interpretation goes beyond the superficial to show the reader what the data suggests, rather than just summarising it.

11.1.2.7 Discussion (suggested word count: 750-850 words)

Some activities to support you with developing evaluation in your Discussion section can be found in Chapter 9 and in lab 7.

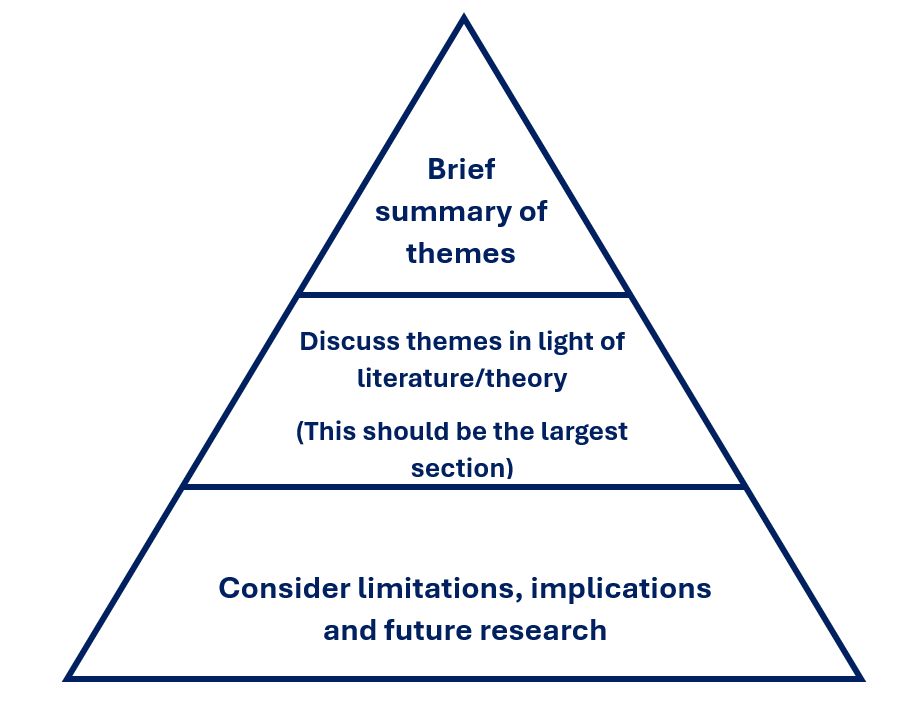

The Discussion is where you bring together your findings and consider these in light of the literature (and theory). It is also where you consider the wider importance of your findings, reflect on limitations and think about potential implications and future directions.

Start with a brief recap

- Remind the reader of the theme/s you report in the Findings and relate these to your Research Question.

Connect your findings to past research

Note: This should be the largest section within your Discussion.

- Here, compare your results with the studies and theories you mentioned in the Introduction, as well as any new studies/theories you want to incorporate.

- Say whether your findings support or contradict those from the literature base. However, also go beyond this and tell us what this means, more broadly. Why might this be important?

- Say whether your findings extend/challenge what is already known. If so, tell us what this means/why it is important, and back your points up with evidence.

It is important to go beyond simple agreement or disagreement, and interpret the data. The following is a ‘not so great’ example:

- “Our theme showed that postgraduate students felt a lot of pressure to succeed, but they did not agree on what “success” actually meant. This is similar to Skye (2023) who said that postgraduates think success means getting good grades, although some thought it meant being a good group member or answering questions in class. Therefore, our results match Skye’s findings.”

This is a stronger example:

- “Our theme showed that postgraduate students feel strong pressure to ‘succeed,’ yet they hold different and sometimes conflicting ideas about what success actually means. This supports Skye’s (2023) finding that, while many postgraduates focus on good grades, others define success through group contribution or speaking up in class. Our findings add to this by showing that it is even more complex, as students tend to hold multiple ideas of success at the same time, creating uncertainty about how to meet expectations. This shows that success is not a fixed standard but something students actively negotiate in response to academic norms and peer pressures. This emphasis on negotiation echoes Isla’s (2025) findings that medical staff similarly construct their professional identities in relation to shifting expectations.”

In the second, the author goes into more depth and explains to the reader what the current findings add. They also then explain this by linking (through the observation that negotiation was key) to a relevant finding from a different field.

Discuss implications

- Explain any practical or theoretical implications of your findings. Remember to make these realistic and linked to your findings.

- Try to make these concrete suggestions, rather than vague statements.

- Remember to back these points up with evidence from the literature base.

Reflect on limitations

- In this length of report, we suggest picking a maximum of one or two limitations, so that you have the opportunity to develop some depth.

- Avoid limitations that are more suited to quantitative studies

- sample size

- lack of generalisability

- Think about limitations that are relevant instead

- The kinds of experiences or voices not represented

- What the research design prioritised or obscured

- How the method of data collection might have shaped interpretation

- As with the other sections, the limitations section is stronger when you clearly link to the evidence base.

Suggest future research

- Show what you would do differently next time and why. Propose ideas for studies that naturally follow from your findings.

- Link to the literature base to support your points.

11.1.2.8 Recap of word count for each section of the report

- Abstract: 100-150 words

- Introduction: 700-800 words

- Method: 350-450 words

- Analysis: 750-900 words

- Discussion: 750-850 words

We understand this can feel like a lot to fit into the report, but it’s a good chance to practise writing concisely. It’s okay to go slightly outside these guidelines, but try not to deviate too much.

A common mistake is making the abstract or method section longer than recommended, which then affects the quality of the other sections.

If you’re struggling with the word count, feel free to drop into office hours. We can’t give general feedback, but you’re welcome to ask specific questions about how you might condense your report.

11.1.2.9 References

Citations in the main body of the text and references in the reference list are structured in exactly the same way as in a quantitative report, using APA 7th style.

11.1.2.10 Appendices

The appendices can often hold a lot of information. In the qualitative report we ask you to include the following in the appendices of the report:

- Required: Your focus group schedule.

- Required: A reflexivity diary that you have developed over the course of completing your analysis. Please use the template linked here to complete your diary.

- There may be other appendices you choose to include. If in doubt, please ask and we will do our best to help.

- Do not include your full transcript or coding as an appendix to your submission 1. We ask each group to submit their transcript to a separate submission port, and you should evidence your individual coding in submission 2 (detailed below)

11.1.3 Submission 2: Step-by-step Evidence of the Analysis Process

We are asking that all students in RM2 complete two separate submissions for their qualitative report.

- Submission 1 = full report with cover sheet and appendices

- Submission 2 = step-by-step evidence of your Reflexive Thematic Analysis

Submission 2 will be formally assessed through the fourth ILO in ‘Evaluation’.

The reasons for this requirement are three-fold:

-

To support your learning of rigorous qualitative research skills.

Reflexive Thematic Analysis (RTA) relies on transparency, reflexivity, and a clear audit trail of decisions. By documenting each step, you gain a deeper understanding of how qualitative analysis works and build skills that are essential for doing high-quality research.

-

To ensure that your submitted work reflects your own analytic thinking.

We know that generative AI tools are now widely accessible, and while they can be useful for support, they cannot replace the reflective, interpretive, and creative thinking at the heart of RTA. Taking the process step-by-step helps you to demonstrate your genuine engagement with the data and protects the integrity of your work.

-

To help you experience RTA as a process, not just a product.

Good RTA is not about producing a set of themes; it is about the journey you take to get there. Keeping a portfolio helps you slow down, think critically, and make your analytic decisions visible. This will lead to richer insights and a stronger final analysis.

In short, we hope that this requirement for keeping a transparent record of your analytic journey will help you produce stronger work and deepen your understanding of qualitative research.

The template can be found here

Answers to some questions

- What advice do you have for completing this process? Our main piece of advice is to work on the reflexivity diary (part of the appendices) and the ‘evidencing the process’ template while you are working on the project. You should be completing these steps anyway as part of the analysis, so it should be a case of logging the evidence as you go. If, however, you do not complete it as you go along, this would make it very difficult to include properly at the last minute.

- Can I use NVivo? For this assignment, no. We plan to develop guidance that considers how students can best use NVivo in the age of GenAI, but this will take some time to develop properly.

- I developed three themes, but can only report two in the qual report itself: What do I do? It probably makes sense to include all of the information up until the end of Phase 4, as often the themes are intermingled together. However, for the Phase 5 part (naming and defining the themes), it is up to you: you can include all of your themes or you can include only those that are in the report.

Below, we have prepared some guidance for each section to help you.

11.1.3.1 Phase 1: Familiarisation

In the template, we ask for your familiarisation notes, when you read through each transcript.

Guidelines for Phase 1

Familiarity notes are brief reflections written while reading and re-reading the data. They are often messy and very personal and are not ‘right’ or ‘wrong’.

They tend to capture:

- First impressions

- What stands out

- What seems confusing or unusual

- Emotional reactions

- Questions or curiosities

- Early ideas about what the participant might be “doing” with their words

- Noticing of tone, contradictions, or patterns

Some things you might note down:

- What immediately grabs your attention?

- How do you feel in response to what you’re reading?

- What do you think the participant is trying to express? Why do you think this?

- Are any ideas or experiences repeated?

- Do they say things that don’t fit together?

- What are you curious about? What would you ask them if you could?

- Anything about their background that shapes how you read this?

- How do your assumptions/interests shape what seems important?

11.1.3.2 Phase 2: Developing Codes

In the template, we ask for you to provide a table with all of your codes in it.

Guidelines for Phase 2

When coding, think about the following:

- Work through your data section by section, thinking about what feels meaningful, interesting or like there is a pattern

- Create short labels (codes) that capture the essence of what each highlighted section is doing, saying, or representing

- Remember that you can be flexible with the coding process. You can create as many codes as you need, and you can merge or rename them later. This allows you to remain responsive as your coding develops over the dataset.

- Try to keep your coding active and interpretive, focusing on meaning instead of counting how often something appears.

- If you are unsure whether to code something or not, err on the side of caution and include it. This will help you avoid overlooking sections that seem contradictory, subtle, or hard to interpret

- Keep a note of your reflections in your reflexivity diary as you code, which will help in later phases.

11.1.3.3 Phase 3: Generating initial themes

In the template, we ask you to a) tell us about your initial themes and/or subthemes, b) tell us the process of how you developed these, and c) tell us about the initial patterns you observed.

In this section, you start to group together your codes into themes. Some parts might come together nicely and others might feel more difficult to put into groups. This is part of the process and nothing to worry about!

Guidelines for Phase 3

When forming your initial themes, think about the following:

- Look across all your codes and identify broader meaning-based patterns.

- Group together codes that seem related, connected, or part of a shared story.

- Notice similarities, differences, tensions, and recurring ideas across your coded data. Sometimes you can have themes that look contradictory on the surface, but there is shared meaning underneath.

- Create rough theme names that capture the central idea or organising concept in each cluster.

- Write a short description of what each initial theme is about and why it matters.

- Write reflections about how you developed the theme (e.g., repeated emotions, shared experiences, contradictions you observed).

- Remember these are initial themes - this is not the final version and they can change, merge, or be dropped in later phases.

11.1.3.4 Phase 4: Developing and Reviewing Themes

In the template, we ask for you to provide details of how your themes changed from the initial themes you identified in Phase 3.

In this section, this is where you really think about what your themes mean, and how they relate to each other. There is often some back-and-forth during this part of the process, and students often end up going back to Phase 3 (or even 2).

Guidelines for Phase 4

- Revisit the coded extracts for each theme and check whether they truly fit together and reflect a coherent idea.

- Look for any extracts that feel out of place, unclear, or better suited to a different theme — or that suggest a new theme.

- Refine each theme’s focus by clarifying its central organising concept: what is the core meaning holding this theme together?

- Check whether themes are too broad, too narrow, overlapping, or repetitive, and adjust by splitting, combining, or renaming.

- Review themes against the full dataset to ensure they capture important patterns across the data, not just isolated points.

- Consider whether any parts of the dataset have been overlooked or require revisiting earlier phases of coding or theme development.

- Make notes about how your themes changed (e.g., merged, refined, expanded) and why these changes improved the analysis.

- Ensure each theme tells a meaningful, distinct part of the overall story you are constructing about the data.

11.1.3.5 Phase 5: Refining, Defining and Naming Themes

In the template, we ask to a) tell us how you came up with your theme names and b) provide a definition for your theme/s.

In this section, this is where you aim to clearly articulate what each theme is about, define its boundaries, and give it a meaningful name that captures its central organising concept.

Guidelines

- Revisit each theme and identify its central organising concept (the key idea that holds the theme together).

- Write a clear explanation of what each theme is about, focusing on the shared meaning across the extracts, not just the topic.

- Know the boundaries of the theme - what belongs in it and what does not? One suggestion is to imagine you are telling someone who doesn’t know your research about your theme. What would you include in such a summary?

- Check that each theme is distinct from the others and not overlapping, repetitive, or too similar in focus.

- Refine the name of the theme so it captures its core meaning in a concise, engaging, and conceptually clear way. Avoid one word theme names or names that are very descriptive.

- Write a brief description of how each theme contributes to your overall analysis.

- Ensure each theme connects back to your research question and supports the analytical narrative you are building.

11.1.3.6 Coded transcripts

Here, we ask that you provide your full coded transcript. This must be completed on Microsoft Word by adding comments.